LDAP Watchdog is a real-time LDAP monitoring script which detects additions, deletions, and changes in an LDAP directory. It provides visibility for those curious to see what’s going on in an LDAP-based environment.

Originally called LDAP Stalker (because it can be used to stalk changes in an LDAP environment like new hires, leavers, promotions, and so on in a corporate setting), LDAP Watchdog is capable of monitoring any changes to an LDAP directory.

Do you want to:

- know what’s going on in your LDAP directory on-demand with Slack webhook integration?

- see new hires, leavers, and promotions as they happen in LDAP?

- monitor when and what HR is doing?

- detect unauthorized changes in LDAP?

- monitor for accidentally leaked data?

- detect when users are logging in and out of LDAP?

Then LDAP Watchdog is for you.

LDAP Watchdog

LDAP Watchdog was built with openldap/slapd environments in mind, and has been tested on Linux. It uses the ldap3 python3 package for retrieving data from the LDAP server. It may or not work on other environments like Microsoft Active Directory (it is completely untested).

The source code, documentation, and instructions on how to use LDAP Watchdog is available on GitHub.

The only really necessary options settings are LDAP_SERVER, USE_SSL, BASE_DN, and SEARCH_FILTER (and LDAP_USERNAME and LDAP_PASSWORD if necessary), and the rest can easily be configured later on during the monitoring stage of using the script.

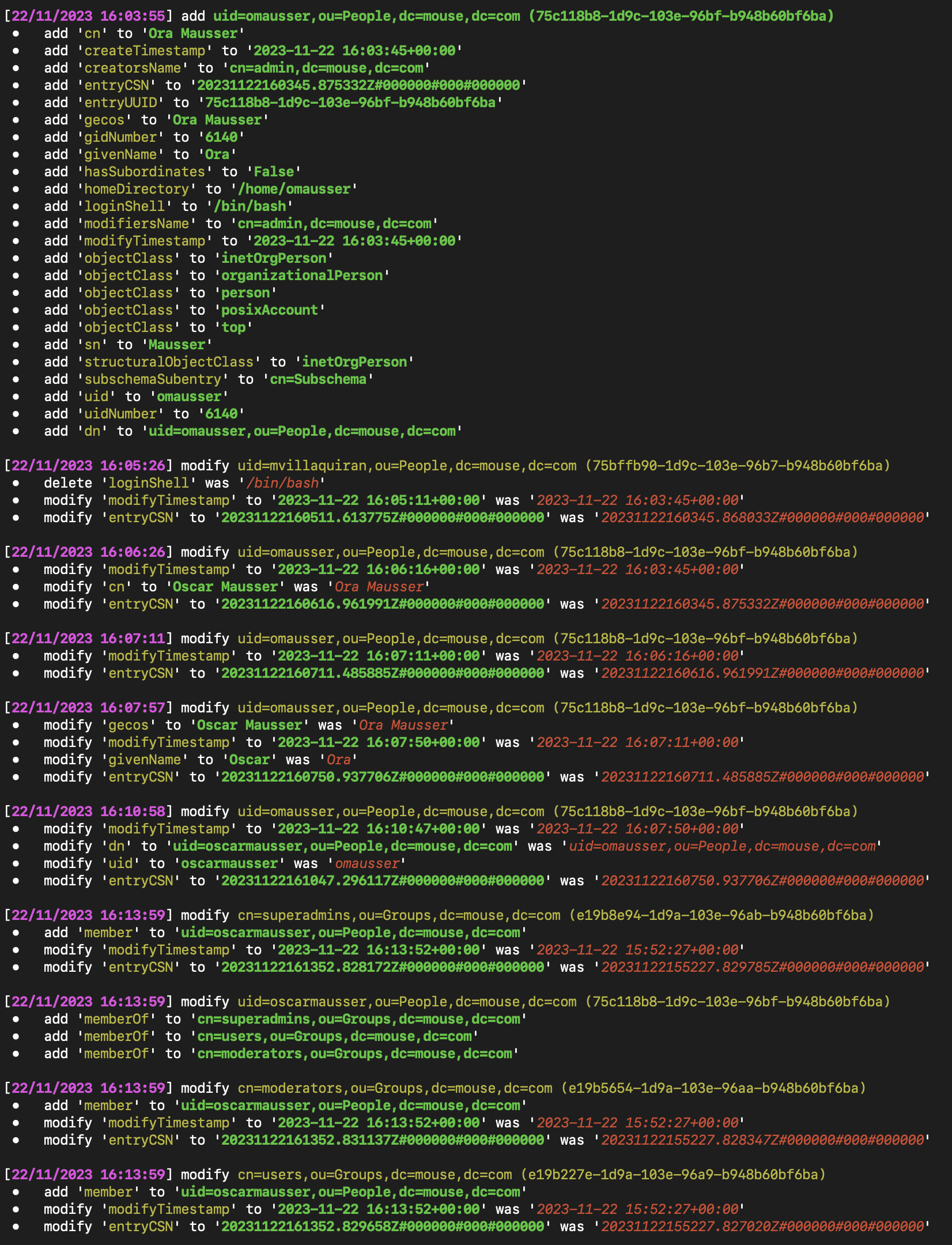

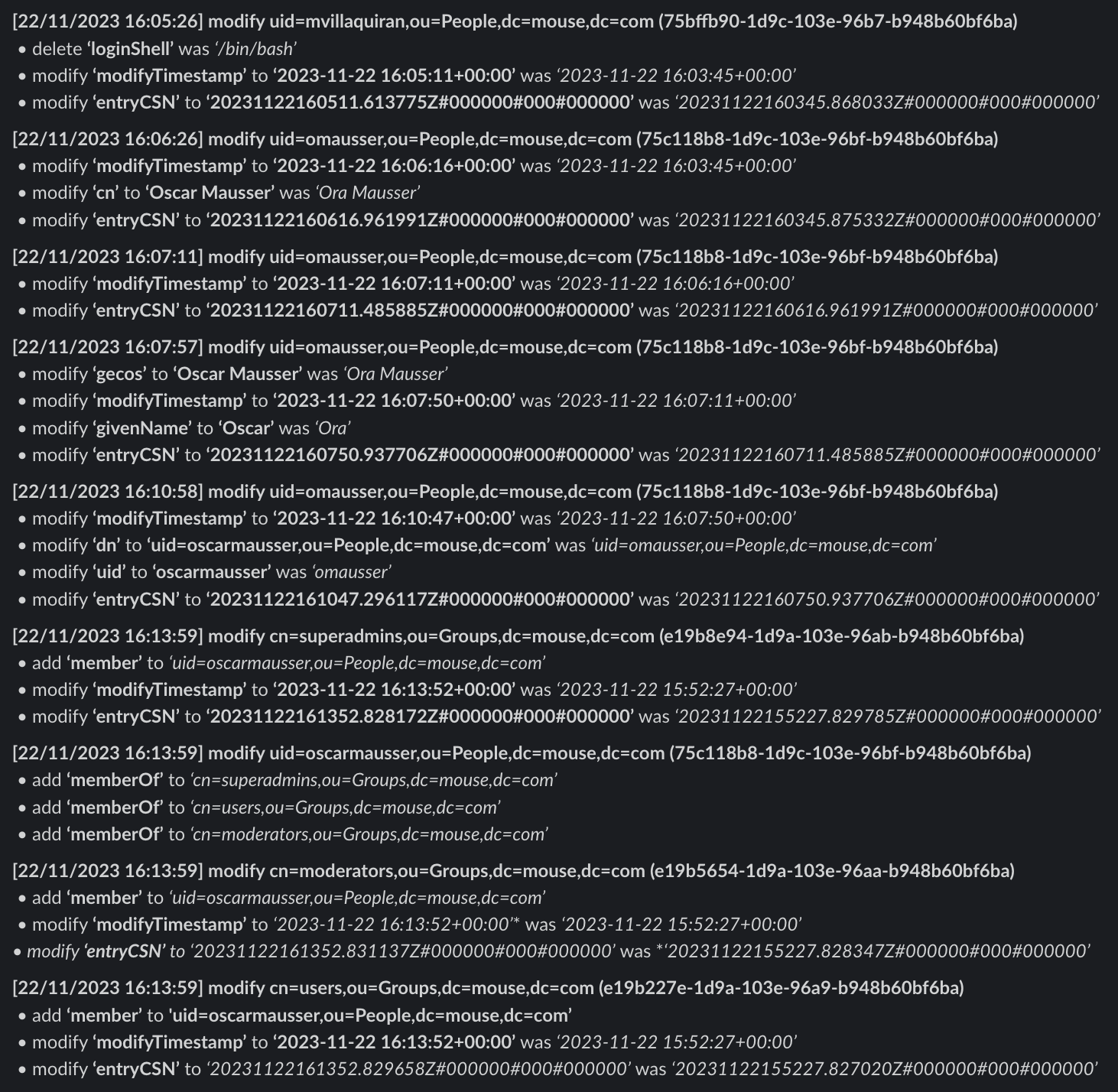

Screenshots

Colored Output:

Slack Output:

Features

- Real-time Monitoring: LDAP Watchdog continuously monitors an LDAP directory for changes in user and group entries.

- Change Comparison: The tool compares changes between consecutive LDAP searches, highlighting additions, modifications, and deletions.

- Control User Verification: LDAP Watchdog supports a control user mechanism, triggering an error if the control user’s changes are not found.

- Flexible LDAP Filtering: Users can customize LDAP filtering using the

SEARCH_FILTERparameter to focus on specific object classes or attributes. - Slack Integration: Receive real-time notifications on Slack for added, modified, or deleted LDAP entries.

- Customizable Output: Console output provides clear and colored indications of additions, modifications, and deletions for easy visibility.

- Ignored Entries and Attributes: Users can specify UUIDs and attributes to be ignored during the comparison process.

- Conditional Ignored Attributes: Conditional filtering allows users to ignore specific attributes based on change type (additions, modifications, deletions).

History

I was looking for some type of tool that I can do to take periodic snapshots of an LDAP directory and monitor and watch the changes that were happening over a certain period. I found LDAPmonitor, but as far as I can tell, it’s only intended for use on Microsoft Active Directory. It didn’t work for what I wanted to do, and looking at the Python source, it seems highly dependent on AD OIDs.

Searching more, I discovered Nick Urbanik’s “LDAP diff”, which compares two LDIF entries and creates a new file which identifies that changes made and the original LDIF which was used/executed by the administrator. An example of how that works is:

$ ldapsearch -o ldif-wrap=no -x -LLL -H ldaps://ldap.local -b dc=rabbit,dc=com '(&(|(objectClass=inetOrgPerson)(objectClass=groupOfNames)))' '*' '+' > ldap.new

$ sleep 360

$ mv ldap.new ldap.old

$ ldapsearch -o ldif-wrap=no -x -LLL -H ldaps://ldap.local -b dc=rabbit,dc=com '(&(|(objectClass=inetOrgPerson)(objectClass=groupOfNames)))' '*' '+' > ldap.new

$ perl ./ldap-diff --orig ldap.old --target ldap.new

dn: cn=superadmins,ou=Groups,dc=rabbit,dc=com

changetype: modify

add: memberUid

memberUid: oscarmausser

dn: uid=oscarmausser,ou=People,dc=rabbit,dc=com

changetype: modify

replace: lastLogin

lastLogin: 1700673781

As we can see, it noticed that there was a modification of dn: cn=superadmins,ou=Groups,dc=rabbit,dc=com and dn: uid=oscarmausser,ou=People,dc=rabbit,dc=com. It even describes the exact change as it would have been executed by the administrator (or system) that made the change. In fact, if you run the script with reversed parameters, you can produce an LDIF which can be used to roll back changes made (fun fact).

After attempting to make a small script to automatically diff an LDAP directory every hour or so, I noticed that the LDAP diff script has a bug: it incorrectly uses the distinguished name as the reference point for comparing entries. Distinguished names can be changed using LDAP’s modrdn operation, meaning the script would erroneously report that the original entry had been deleted, and a new record had been created (with all of the deleted record’s data and a different distinguished name). Instead, the operational attribute entryUUID should be used: it is a unique identifier for the entry. I’ve fixed that bug and released a patch on GitHub.

Personally, using a Perl script which I don’t really understand simply isn’t a possibility for me; mentally, at least. Therefore, I decided to just make what I originally wanted: a script that would notify me of changes to an LDAP directory as they happened. LDAP Stalker (renamed to LDAP Watchdog) was thus born.

Development

The script itself isn’t anything too interesting, but it was quite tedious to work with so many nested loops. At one point, there’s a 5-nested-for-loop. The comparison function is highly commented (necessary due to the labyrinth of for-loops).

Basically, we create three dictionaries for modifications of an LDAP entry (i.e. the entry (such as a user) already exists, but the attributes of this entry have changed).

changes["additions"] = [

{ attr_name: [val1, val2, val3, ...] }

]

In the above example, values have been added to the attr_name attribute – this attribute may or may not have already contained values; all this states is that for the entry, the attribute attr_name has three new values: val1, val2, and val3 (i.e. it does not mean that attribute attr_name has only three values).

The above dictionary works the same way for removals:

changes["removals"] = [

{ attr_name: [val1, val2] }

]

The attribute attr_name now does not contain val1 or val2. Again, this doesn’t tell us anything except that the values were deleted: it especially doesn’t tell us whether attr_name is now empty for the entry.

Modifications of attributes were a bit more difficult. We define a modification for attributes which have only a single value, and that single value has changed from one value to another:

changes["modification"] = [

{ attr_name: [val1, val2] },

]

Here, the attr_name attribute of the entry has been changed from val1 to val2. In reality, it’s possible that the attribute was actually deleted and then added again: but after all, is that not what a modification is?

The above three dictionaries are all dictionaries of sets of dictionaries. I’m no longer sure whether the ‘sets’ part here is necessary. It was originally intended to avoid situations where an attribute had multiple additions or removals, when the dictionary used to look like:

changes["removals"] = [

{ attr_name: val },

{ attr_name2: val2 }

....

]

When the dictionaries worked like that, if a single attribute had multiple removals or additions, only the final one would be saved. However, since additions and removals now use sets for the added/removed values of each attribute, it doesn’t look like it’s needed any more. This is something that can be improved in the future.

Maybe it’s also a bit interesting that binary-formatted attributes (like images?) are represented in a special way by python’s ldap3 module. If the attribute’s value is in a binary format, it becomes represented by a dictionary with two keys:

entry_dict[attr_name] = {

'encoded': base64_string,

'encoding': 'base64'

}

The script automatically sets entry_dict[attr_name] = entry_dict[attr_name]['encoded'] in this case.

The only other interesting functionality is that before sending a Slack message, the script automatically checks whether the message it’s going to send it too long. If it is, it finds the largest word/string (separated by a space) in the message and replaces it with “[…truncated…]” – repeating this until it is short enough to be submitted to Slack.